To many in his hometown of Washington, D.C., during his 1980s reign as the city’s biggest cocaine and crack dealer, Rayful Edmond was public enemy number one. At the height of Dodge City’s brutal crack epidemic in 1987, this 22-year-old man was responsible for distributing 60 percent of the cocaine that flooded the city’s streets. In the Chocolate City, Rayful was the undisputed king of cocaine. He was street royalty with a certified gangster resume.

To many in his hometown of Washington, D.C., during his 1980s reign as the city’s biggest cocaine and crack dealer, Rayful Edmond was public enemy number one. At the height of Dodge City’s brutal crack epidemic in 1987, this 22-year-old man was responsible for distributing 60 percent of the cocaine that flooded the city’s streets. In the Chocolate City, Rayful was the undisputed king of cocaine. He was street royalty with a certified gangster resume.

At his peak Rayful sold 2,000 keys a week, reaped gross profits of $70 million a month and ran an operation with over 150 soldiers to support him. By his early twenties he had established himself as the city’s most notorious drug kingpin. In the high profile and glamorous life he led, champagne flowed like water, trips to Las Vegas, New York and Los Angeles were commonplace and $50,000 shopping sprees were the routine. Rayful personified the big city drug lord and his stature epitomized all the accolades that position demanded.

To the mainstream media, he encompassed all that was wrong with the city’s crack epidemic, but in the streets Rayful was a hero, an inner-city gangster who made it to the top echelons of the drug trade. A Lucky Luciano, Billy the Kid-type figure. But there were consequences to his reign. His volcanic rise coincided with an unprecedented explosion of street violence and drug addiction in the capital city. The era is remembered for murder, mayhem and bloodshed. Historians have blamed the crack storm that seized D.C. on Rayful, but Rayful maintained he was only trying to help his family live a better life and enjoy the finer materialistic trappings of capitalism that were often denied denizens of the ghetto.

To the block huggers, four corner hustlers and hood mainstays Rayful was beloved, even worshipped. His appeal crossed boundaries and he was adored by children and adults alike. But to others he was feared, a man who wreaked havoc on his community. Neighborhood people saw the effects of his crack enterprise outside their front doors and it wasn’t pretty. A community divided was in essence, a community destroyed. But regardless of what people thought of Rayful, he was an enigma, the president and CEO of what authorities called “the largest network for cocaine street sales in Washington D.C.” He was a gangster legend of epic proportions, until he tarnished his legacy by turning snitch.

Part 8 In Prison

“Through history, all the bad things happened to the good guys,” Rayful said. “So I’m a good guy and just something bad happened to me and I’ll overcome it sooner or later.” But Rayful was in prison staring multiple life sentences in the face. His prospects were bleak, but he tried to make the best of a bad situation. “I will be home one day soon in a couple of years after my appeal,” Rayful said. “We will all be home in a couple of years. I’m not a violent person. You can ask 1,000 people. In high school I was only in two or three fights. I was tried for murdering one of my best friends. Ask his family. They got to see that I ain’t no murderer or nothing. Maybe I was a drug dealer, but I’m not all that bad of a person.”

Exactly who and what Rayful was caused a lot of disputes in the Chocolate City. One woman, quoted anonymously in The Washington Post said she was pleased by the conviction because Edmond was responsible for “a whole lot” of bad things that happened to children with drugs. But a man recalled that Edmond gave his family money for flowers when a brother died and occasionally gave extra money for medicine and bus fare. “He may have been guilty of knowing the wrong people,” the man said. “But Rayful wasn’t no dope pusher.” The director of a recreation center said the neighborhood children would miss Edmond. “They looked up to him. They respected him. If they ever had any problems, they could come and talk to him. They saw him as a big brother.” He said.

Despite his life sentence without parole, Edmond was making plans for when he got out. He dreamed of opening a nightclub. In one room he would have big movie screens. In another room there would be pool tables. And in a special room, people could watch “like nasty movies.” There would be a room for dancing and “a bar where they could buy all they want or whatever they want.” There would be a dress code, “casual shoes, slacks and a jacket.” Rayful knew it would be a success. “I could just put my name up there and people just come because they say ‘Oh, that’s Rayful’s club.’” Rayful was a little delusional to say the least.

Edmond’s long term home was a small cell at U.S.P. Marion. He described U.S.P. Marion as a place where prisoners wanted to take their frustrations out on each other. “I wish I was in another institution,” Rayful said. He explained that U.S.P. Marion was for the most dangerous criminals and that he wasn’t violent.

“I wouldn’t wish this place on anybody.” He said. When he wanted to hear the sound of another voice he had to call out carefully in a low voice, because he didn’t want to risk having another prisoner tell him to shut up, an act of disrespect he’d have to respond to.

“In Marion you just really don’t have too much communication,” he said. “And sometimes you feel lost and then the people, they not really functioning right. People tend to age a lot at Marion, they worry. They don’t wanna be here. People be loving their families and they can’t call them. It’s lonely here.” Rayful couldn’t call his family anyhow, because they had been spread far and wide, to prisons as distant as California.

“I’m going through the hardest,” Rayful said. “Probably harder than anybody else been through, but I don’t let it bother me. I just try to be me, just be Rayful. Like a lot of people come to jail and they get caught up into what’s happening in the institution, but that’s not what life is about. Life’s about being free and living in the streets. “If I ever went home, I would never come back. I’m just here until one day when I catch a break, get back in court and maybe get some of the time back and have a date to go home. I just be thinking of that. I’ll get out in a couple of years from now, probably two years.” But Ray was dreaming.

“Everybody is trying to make it seem like drugs is all that bad. I’m saying it is bad, when it gets to the kids that don’t know what it is. It’s bad. But when you of age, it’s not bad. When you of a certain age, it’s not bad. When you of age you make your own judgment.” Rayful said.

“People abuse anything in life. Like men have good women and they abuse them. People have nice kids and they abuse their kids. So that’s just part of life and a way of life. People be trying to survive, then you got a lot of money, so somebody might try to rob you and kill you. Drugs are all over now. That’s just life. They are everywhere.

“I would say white people are more conservative and tend to handle it a little better than black people. Maybe their system be a little stronger as far as with drugs. I don’t try to judge people. People just look for ways to survive. And if drug dealers do wrong, their intention is not to hurt anybody, not to hurt kids.

“People just say, ‘Drugs are bad.’ But it’s so many people that are out there talking about, ‘Drugs is bad,’ that are using drugs themselves. Just like Marion Barry. All this stuff he going around talking about drugs this, drugs that. I’ve been locked up for years and the streets are worse than ever. If I was the problem everything should have been cleared up by now.”

In 1990, after a short stint at U.S.P. Marion, Rayful was transferred to U.S.P. Lewisburg where he had more freedoms like walking the yard, using the phone and having the run of the compound. Not much, but better than 24 hour lockdown. U.S.P. Marion was the maximum security prison in the federal system while U.S.P. Lewisburg was only a high security institution. Rayful settled in nicely to the less restrictive environment.

In 1990, after a short stint at U.S.P. Marion, Rayful was transferred to U.S.P. Lewisburg where he had more freedoms like walking the yard, using the phone and having the run of the compound. Not much, but better than 24 hour lockdown. U.S.P. Marion was the maximum security prison in the federal system while U.S.P. Lewisburg was only a high security institution. Rayful settled in nicely to the less restrictive environment.

“He came in with great accolades,” an old time mobster who was at the prison when Rayful came in says. Lewisburg is a very gothic style prison, like an old English castle. Hawks and other birds of prey inhabit the steeples built into the structure. Also there is a historical wall that can’t be altered. The wall is 50 feet high. The population at Lewisburg when Rayful arrived consisted of Italians, Asians, blacks and Irish. All the major ethnic groups were represented and Lewisburg was a hub of criminal activity as it is located between all the major East Coast cities and the most densely populated areas.

“All illicit activities are going on there because all the major cities are a stone’s throw away,” the old time mobster says. “The prison housed some of the most famous prisoners of the United States from Jimmy Hoffa to John Gotti to biker leaders from the Outlaws, Pagans and Hell’s Angels. Big drug dealers from all the major cities were there including Peanut King, Little Melvin, Big Melvin Stanford, Cadillac, the Nicky Santoro crew, Sam the Plummer’s crew, Jimmy “The Gent” Burke, members from all the five families, the big Colombian dealers and a lot of guys from the Raymond Patricia family, Frank Valente, Angelo Leonardo and Joe Gallo. John LaRocca’s Pittsburgh family with Nick the Blade and the Philly Nicky Scarfo crew were there. The gangs weren’t popular then.”

Ray quickly took advantage of the situation. He learned that it was even easier to deal drugs from behind bars to people on the outside. He had access to phones on the B cellblock practically whenever he wanted. There was the mail and there was his full contact visits. All privileges he didn’t have at Marion. He got his visitors to smuggle small amounts of cocaine, heroin and marijuana in to him.

“Those were the basic four: cocaine, crack, heroin and marijuana,” he said. Rayful brought the drugs in through the visiting room. He hired other prisoners, whose girlfriends, during contact visits, would pass the drugs packed in small balloons. It was a simple routine. The oldest trick in the book.

“She might kiss him, and he put ‘em in his mouth. Got ‘em all inside. Then he get back inside the institution, he spit ‘em up. I’ve seen somebody bring in like 60 balloons before. It keeps the jail mellow. Keeps people patient. They be able to get high and chill.” Rayful said.

Lewisburg was the center of criminal activity on the East Coast. When you have a bunch of people of such a high magnitude from the criminal underworld in one place illicit activities are going to occur. “Drugs were so prevalent people developed bad drug habits to wash away the memory of their sentences,” the old time mobster says. “There were crap games, alcohol- homemade or smuggled in, every drug imaginable. They even had a Monte Carlo night, where you could play blackjack or dice like in a casino.”

Making the most of his circumstances, Edmond reinvented himself, becoming a broker- bringing inmates with sources of cocaine together with his friends and associates back home who had the customers. “I wanted to make more money,” Edmond said. “At that time my mindset was I had to still have people look up to me and prove that I was still capable of making things happen.”

Ray wasn’t in Lewisburg two weeks before the FBI started getting reports that he was still dealing. The clever Edmond just moved his office to the penitentiary. He was doing the same thing from prison. And he found dealing drugs was even easier from prison.

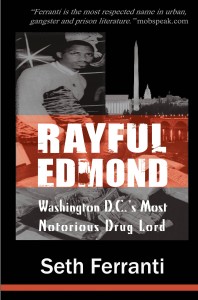

This is an excerpt from Rayful Edmond: Washington DC’s Most Notorious Drug Lord – Order it from Gorilla Convict in print or ebook versions.

Also check out the book trailer on YouTube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tT1jxTjsbQw