It’s been a long time coming, but finally it seems our government is realizing that the War on Drugs has run its course and that we can’t incarcerate ourselves out of the drug problem. During the urban crime crisis of decades ago, federal and state governments cracked down on crime. Tough measures, such as harsh sentencing laws, led to an eight fold increase in the federal prison population since 1980. These laws helped lower crime rates, but the increase in incarceration was expensive and imprisoned some people for longer than they deserved.

It’s been a long time coming, but finally it seems our government is realizing that the War on Drugs has run its course and that we can’t incarcerate ourselves out of the drug problem. During the urban crime crisis of decades ago, federal and state governments cracked down on crime. Tough measures, such as harsh sentencing laws, led to an eight fold increase in the federal prison population since 1980. These laws helped lower crime rates, but the increase in incarceration was expensive and imprisoned some people for longer than they deserved.

As the Drug War has raged full throttle millions of people have been locked up, hundreds upon hundreds of prisons have been built, a virtual cottage industry has been created to supply and service correctional systems nationwide and Congress and state legislatures have enacted a one size fits all sentencing regime, that largely convicts low level drug offenders and sentences them to prison for decades of their lives with no chance of parole.

As a result, the prison industrial complex has become a powerful player in Washington DC political circles. Incarceration has become more about the bottom line than justice. So Attorney General Eric Holder has been using the powers of the justice department to reform how the federal government punishes drug offenders. Last week he asked the US Sentencing Commission to help. But Congress is best situated to reform sentencing policy. The laws must change before the Commission can do much more, and there are limits to the discretion Attorney General Holder can or should use. With the powerful prison lobby having Congress’ ear, changing the drug laws has been a tough battle.

The correction business has a lot of power and their business has been booming since the mid-90s. Due to that fact, a whole bunch of industries have grown up around correctional services, catering to the bloated and corrupt entity that the modern prison industrial complex has become. But finally, almost three decades into the War on Drugs, the tide might be turning.

“The main drivers of prison growth are front end sentencing laws enacted by Congress, like the proliferation of mandatory minimum sentences,” said Senator Patrick Leahy (D-VT), chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee. “I am committed to addressing sentencing reform this year, as I know other senators are from both sides of the aisle. It is a problem we created and it is time that we fix it. Public safety demands it.” The growing interest in legislative action already constitutes an abrupt change in the United States’ decades old tough on crime approach and would include dialing down on the long criticized mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines for a range of nonviolent crimes.

Leahy’s remarks came after the House of Representatives saw the introduction of a key legislative proposal called the Smarter Sentencing Act. The fact that politicians are talking about and acknowledging the problem is the first step, but this change has to constitute much more than rhetoric. Everyone knows that politicians, like prosecutors and most lawyers cannot be trusted. Any changes to mandatory minimum sentences will be an uphill battle, but at least Leahy and others seem to be joining the national conversation and debate.

The senator is making the push to move forward on a landmark overhaul of the US criminal sentencing guidelines that would aim to significantly cut down the bloated population in federal prison. More importantly, several new and pending proposals have gained widespread support from all across the political spectrum, leading many observers to expect some sort of legislative action on a major policy issue, a rarity in today’s polarized Congress.

Mandatory minimum prison sentences for drug dealers were once viewed as powerful levers in the nation’s war on drugs, a way to target traffickers and punish kingpins and masterminds. But Congress, which approved the law in 1986, when crack fueled crime gripped America’s inner cities, is now grappling with a present day, lower crime reality and the questions that were raised at the onset of the draconian laws are being asked more frequently and with much more fanfare today. Have the mandatory sentences put the wrong sort of offenders in prison for too long and at too high a cost for the nation to beat both literally and figuratively?

Mandatory minimum prison sentences for drug dealers were once viewed as powerful levers in the nation’s war on drugs, a way to target traffickers and punish kingpins and masterminds. But Congress, which approved the law in 1986, when crack fueled crime gripped America’s inner cities, is now grappling with a present day, lower crime reality and the questions that were raised at the onset of the draconian laws are being asked more frequently and with much more fanfare today. Have the mandatory sentences put the wrong sort of offenders in prison for too long and at too high a cost for the nation to beat both literally and figuratively?

The US Sentencing Commission has long held that a broad rebalancing of the nation’s criminal justice system was needed. Its current plan is to reduce the severity of changing recommendations for a variety of lower lever drug crimes. Though tough minimum sentencing guidelines were supposed to be aimed at bigger fish, the Commission found that they often netted minnows, catching couriers and males rather than suppliers and organizers. Half of the federal cases in 2009 were brought against people in the lower rungs, and they were still subject to the mandatory minimum penalties.

“The legislation could ultimately save our country billions of dollars in prison costs while keeping us safe,” Attorney General Eric Holder said. “I look forward to working with members of both parties to refine and advice these proposals in the days ahead.” Under discussion are proposals that would cut minimum sentences by half, give judges more sentencing discretion and retroactively apply new crack cocaine sentencing standards to prisoners convicted under previous requirements. Also being considered are in prison programs that could help nonviolent inmates earn early release.

A bill sponsored by liberal Democrat and majority Whip Richard Durbin (D-IL) and Tea Party Republican Mike Lee (R-UT) would cut the 5, 10 and 20 year minimums now required for first and second drug sale offenses. Separate legislation offered by Republican Rand Paul of Kentucky and Leahy would give judges the ability to impose sentences short of the minimum guidelines.

Additionally Senators Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) and Rob Portman (R-Ohio) have proposed allowing inmates to shorten their sentences by participating in re-entry programs and Senate Minority Whip John Cornyn (R-TX) has introduced a bill that would allow low risk prisoners to serve up to half of their remaining sentences in home confinement or a halfway house.

Leahy said he is “encouraged by the progress being made to reach a bipartisan and comprehensive compromise of sentencing reform that includes important changes to mandatory minimum sentences.” But the momentum behind the proposal has faltered at times.

Durbin has faced hesitation on the plan from committee Democrats such as Dianne Feinstein of California and Charles E. Schumar of New York, while Lee has encountered resistance from panel Republicans like Charles E. Grassley of Iowa. But Senate Judiciary Republicans such as Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Jeff Sessions (R-AL) are open to legislation and most Democrats are expected to be supportive.

In a different, but related development, 2014 saw the US Sentencing Commission suggest amendments to the US sentencing guidelines that would lower the recommendations for drug trafficking sentencing. “The Commission’s proposal reflects its priority of reducing costs of incarceration and overcapacity of prisoners without endangering public safety,” said Judge Patti B. Saris, Chairman of the Commission.

“Like many in Congress and in the executive and judicial branches, the commission is concerned about the growing crisis in federal prison populations and budgets and believes it is appropriate at this time to carefully reconsider the sentences for drug traffickers, who make up about half of the federal prison population. Our proposed approach is modest. The real solution rests with Congress and we continue to support efforts there to reduce the mandatory minimum penalties, consistent with our recent report finding that mandatory minimum penalties are often too severe and sweep too broadly in the drug context, often capturing lower level players.”

The historic proposed amendments which include an across the board reduction in the sentences recommended for all drug offenses is a very important step and a sign of the times. With this reduction, the sentencing guideline penalties for drug traffickers would be lowered by two levels at the base offense levels in the drug quantity table and would result in approximately 11 months off for those offenders who would benefit. It could affect almost 6,550 inmates.

But the mandatory minimums would essentially stay the same; just the higher end of the guideline range would be lowered. Still the proposed amendment, which becomes official in November 2014, with the commission having the authority to make it retroactive, is a terrific and fitting application of some of the themes that been stressed by many members of Congress and by the Attorney General.

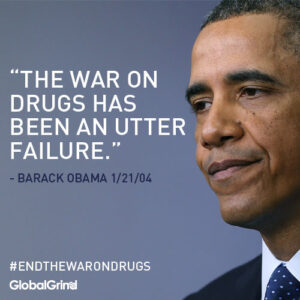

“If I told you that one out of three African American males are still prevented from voting because of the War on Drugs, you might think I was talking about Jim Crow 50 years ago,” Senator Paul said. Lawmakers, criminal justice officials and analysts have said there is a growing philosophical component to this seismic shift that is raising fundamental questions of fairness. For the first time in a generation politicians are collectively acknowledging that some of the most extreme punishment policies have largely failed.

“If I told you that one out of three African American males are still prevented from voting because of the War on Drugs, you might think I was talking about Jim Crow 50 years ago,” Senator Paul said. Lawmakers, criminal justice officials and analysts have said there is a growing philosophical component to this seismic shift that is raising fundamental questions of fairness. For the first time in a generation politicians are collectively acknowledging that some of the most extreme punishment policies have largely failed.

“There is something really profound going on,” David Kennedy, Director of the Center for Crime Prevention said. “There is movement on mandatory minimums, there is movement on solitary confinement, there is movement on the death penalty. What ties them all together is the basic recognition that the application of power with justice is brutal. And there is nothing democratic about brutality. This has been an evolutionary process. People are now recognizing that the business of corrections is not really limited to incarceration.”

Attorney General Holder has called on Congress to pass the bipartisan legislation currently taking hold in the Capital and is optimistic about the bill’s chances. But there have been a number of dissenters who have held up the mandatory minimums as good for our nation. “The real power and efficacy of federal minimum mandatory sentences is our ability to hold them over certain people’s heads in solving kingpin drug cases or major murders,” said Scott Burns, head of the National District Attorneys Association. The sentencing rules have been “an important tool” in driving down serious crime, Burn said, which over the past three decades has plummeted. He sees Congress1 motivation as purely financial. “They’re doing this because they are simply refusing to fund more federal prisons, period.”

Dwindling public resources have jumpstarted a movement, as stressed government budgets were unable to keep pace with the rates of prosecution and incarceration. It costs the United States about $80 billion per year to house more than two million people in jails and prisons. Many prosecutors oppose leniency, arguing that tough sentencing guidelines give them more leverage. That’s true, but it’s no defense of punishments that are tougher than they should be.

The truth of the matter is federal prosecutors use the harsh sentences as a cudgel to elicit guilty pleas. A Human Rights Watch study released says that the Justice Department regularly coerces guilty pleas in federal drug cases by threatening long sentences. And Attorney General Holder weighed in on the matter also, announcing that the Justice Department would not pursue mandatory minimum sentences in cases involving low level, nonviolent drug defendants.

The truth of the matter is federal prosecutors use the harsh sentences as a cudgel to elicit guilty pleas. A Human Rights Watch study released says that the Justice Department regularly coerces guilty pleas in federal drug cases by threatening long sentences. And Attorney General Holder weighed in on the matter also, announcing that the Justice Department would not pursue mandatory minimum sentences in cases involving low level, nonviolent drug defendants.

“We must ensure that our most severe mandatory minimum penalties are reserved for serious, high level or violent drug traffickers.” Holder said. Holder also noted that President Obama has entered the sentencing debate by commuting the sentences of eight crack cocaine offenders “who were sentenced under the outdated sentencing regime.” President Obama has also discussed the need to reform how individuals are prosecuted for marijuana, considering the new laws in Colorado and Washington, legalizing recreational marijuana.

In a fitting end to all the rhetoric the US Senate Judiciary Committee took the first step in righting the wrongs of the drug wars by passing the first major reconsideration of federal mandatory minimum drug sentencing laws since the Nixon administration. The Smarter Sentencing Act has been called the biggest overhaul in federal drug sentencing ever. The act aims to reduce the federal prison population, decrease racial disparities, save taxpayer money and reunite nonviolent drug offenders with their families.

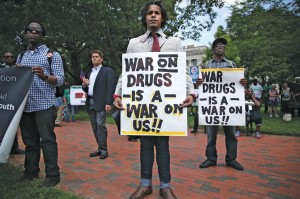

The legislation is opposed by a number of US prosecutors who continued to defend the harsh, racially unjust system that led to a greater percentage of black men being locked up in the US, than in South Africa at the height of Apartied. Part of the act addresses the issue of over criminalization and the fact there are too many federal crimes that people can and do break unknowingly and unintentionally. These violations could be better addressed with fines, rather than prison time.

A group of federal prosecutors has criticized the bill. The National Association of Assistant United States Attorneys, an organization representing about 1300 of the 5600 federal prosecutors objected to the Smarter Sentencing Act. NAAUSA president Robert Gay Guthrie urged that the US should resist calls to reform its mandatory minimum laws, which require judges to sentence drug defendants to lengthy prison terms, even if the judge considers those sentences excessive. Guthrie insists that the “merits of mandatory minimums are abundantly clear,” insisting that they reach “only the most serious of crimes” and “target the most serious criminals.”

But anyone familiar with the federal drug laws and the cases prosecutors bring up know that is some bullshit. We can only hope that the tide keeps turning. Prosecutors like Guthrie represent just the type of overzealous prosecutors that have corrupted the drug laws Congress enacted, using them on low level, nonviolent offenders just because they wouldn’t cooperate or because they didn’t have anyone or know anyone to cooperate against. It’s about time the balance of power shifted back to the judge.

Prosecutors with their win at all costs mentality have cast aside justice and the essence of what is right or wrong, using laws meant for Pablo Escobar on college kids and urban youth who run small time drug operations. It has been a slow and arborous process, but maybe just maybe, all those buried in the belly of the beast will get some form of relief from the unjust and draconian sentences they have been forced to serve and that their families have been made to endure.