The Beginning of the Mexican Cartels- During the early 1980s, the Medellin cartel ran the bulk of its cocaine into North America through Florida. It was nine-hundred-miles from Colombia to Florida. Planes would drop water-proof loads of coke into the ocean off Florida. Forty foot speedboats – called go-fast boats – would pick it up and dash ashore with their valuable contents. At other times, the planes would simply drop their loads onto the interior of Florida, where it would be met by trucks.

Because of the amount of money at stake – billions of dollars – violence erupted in Miami-Dade County, as local distributors competed with one another. Griselda Blanco was one such distributor. Hailing from Colombia, Griselda Blanco began her criminal career as a child prostitute, and then graduated to kidnapping. Seeing her chance, she moved to Florida, where she pushed cocaine. Being a hardcore psychopath, murder was Griselda’s default mode. Her tendency for killing secured her nickname – the Black Widow.

The violence got so out of control that in 1982 President Ronald Reagan decided to do something about it. Reagan gave approval for the South Florida Task Force. The mission of the Task Force was to slug it out with the drug lords. The Task Force composed of the FBI, along with elements of the army and navy, employed surveillance planes, helicopters, and boots on the ground. Seizures of drug shipments accelerated. The Medellin cartel lost millions of dollars. The cartel realized that something needed to be done. It was either do something or go out of business.

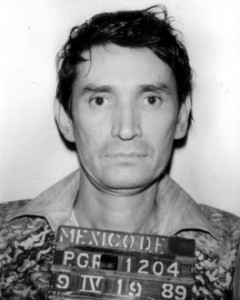

Forced to find another way to move cocaine into the U.S., the Medellin cartel decided to go overland. The cartel contacted Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo, the Mexican Godfather. Gallardo, born in Culiacan, Sinaloa, began his business career as a young boy, hawking chickens and sausages. Later, Gallardo joined the Federales, the Mexican national police. Hired as a bodyguard for Leopoldo Sanchez Celis, who was the governor of Sinaloa, Gallardo met Pedro Aviles Perez, another of the governor’s bodyguards. Perez moonlighted as a drug smuggler, controlling most of the marijuana and heroin smuggled into the U.S. Perez was an innovator, being the first to use planes to transport drugs, along with liberal bribes to officials. Perez liked Gallardo. He took the young man under his wing and taught him the ins and outs of drug trafficking.

During a shootout with the Federales in 1978, Perez was killed. Gallardo inherited the business, moving his product into the U.S. through Tijuana. Because of his iron-fisted control over his kingdom, Gallardo was known as the Godfather. The DEA was aware of Gallado, but didn’t know how powerful he was. In 1984, a DEA agent infiltrated Gallardo’s gang. The agent’s name was Enrique ‘Kike’ Camarena. Kike chummied up to Gallardo, while simultaneously providing intel to the DEA. Because of Kike’s intel, the DEA convinced the Mexicans to launch a major offensive in remote Chihuahua. With a force comprising 450 Mexican soldiers supported by armed helicopters, the Mexican army hit Rancho Bufalo, which was a 2,500 acre marijuana farm. Rancho Bufalo was owned and operated by Gallardo. The farm was decimated.

Gallardo smelled a rat. Something was fishy in Denmark. A meeting was called. All the major players arrived and discussed the situation. Later, another meeting was held. All evidence pointed to Kike.

Kike and his pilot, Alfredo Zavala Avelar, were leaving the American consulate building in Guadalajara, when five gangsters attacked them, threw jackets over their heads, and tossed them into a waiting Volkswagen van. One month later, the bodies of Kike and Avelar were discovered hundreds of miles away, in Michoacan. The corpses were decomposing, hands and legs still bound. Obviously, both men had been tortured and mercilessly beaten; a stick had been inserted in Kike’s rectum. Autopsy revealed that Kike had died when his skull was caved in by a blunt object.

Later, after an intensive investigation, the DEA discovered the five gangsters responsible for Kike’s abduction were not gangsters. They were Jalisco police officers. The five officers were arrested by the Federales and interrogated. All five officers confessed their part in the kidnapping, signing written confessions. The confessions resulted in the arrest of eleven more individuals. Warrants were issued for Rafael Caro Quintero and Ernesto Carrillo. Rumor had it that Quintero was behind the killing of Aviles Perez, whose death allowed Felix Gallardo to take control of Perez’s drug kingdom. The DEA pursued Quintero, who they found in Costa Rica. Special Forces arrested Quintero and extradited him to Mexico, where he was interrogated. Quintero’s interrogation didn’t take long; he spilled the beans, admitting he had planned the kidnappings.

The Mexican army found Ernesto Carrillo in Acapulco, where they arrested him. Carrillo also confessed to the kidnappings, but denied participation in Kike’s torture and murder. Eventually, the DEA pinpointed a house in Guadalajara, where the two men had been tortured. The DEA came away from the entire episode with a bad taste in their mouths. Events had exposed just how corrupt Mexico was. Evidence had been deliberately destroyed, obscured and withheld.

Meanwhile, Gallardo had to find a new source of money. After the destruction of Rancho Bufalo, Gallardo’s revenue flow had all but stopped. Gallardo hooked up with Juan Ramon Matta Ballesteros, a curly-haired drug lord from Honduras. Matta had his own revenue problems. At the time, Matta was cozy with Pablo Escobar, the head of the Medellin Cartel. Escobar, too, had a problem. Escobar was looking for a solution to his problem, the South Florida Task Force, which was making his business model more and more difficult. Escobar’s business model worked like this: drugs go out, money comes in. But because of the South Florida Task Force the model went something like this: drugs go out; drugs are confiscated; no money comes in. Matta was tasked with the job of finding a new business model for the Medellin Cartel.

Matta, who was very charismatic, decided that Gallardo’s Sinaloan gang was the remedy to the Medellin Cartel’s problem. The Mexicans knew how to move drugs across the border into the U.S. The smuggling methods and routes were in place. And the Sinaloans had the men and know-how to move lots of product. All the Colombians had to do was give the coke to the Mexicans, who would then transport it into the U.S. The border was 2,000 miles long, which meant it was very hard to effectively patrol.

Matta brokered a deal. On their part, the Colombians would provide cocaine to the Sinaloans, who would transfer it north of the border. Once in the U.S., the Colombian distributors would pick it up and sell it. It was a win-win business deal. The Colombians would move product and make money; the Sinaloans would smuggle and make money, lots of money, especially since Gallardo insisted on being paid cash for the services of his gang.

It worked like a charm.

Eventually, so much cocaine was being moved by the Mexicans that they had difficulty storing the cash. There were literally boxcars of money. In other words, everything was just peachy. But then Gallardo had an idea. Rather than being paid in cash, he could demand payment in product, cocaine. And that’s just what he did. The Colombians didn’t balk. They couldn’t. They had no choice in the matter. Florida was too risky. The DEA was seizing shipments left and right.

Overnight, Felix Gallardo and the Sinaloan gang became cocaine kings. They weren’t just couriers anymore. Now they were players, moving their own product as well as that of the Colombians. The Sinaloans went from the minor leagues to the major leagues in a single leap. In the drug trafficking world, Felix Gallardo transitioned from the role of supporting actor to movie star. The DEA began keeping close tabs on Gallardo, elevating his position on their Christmas Wish List.

Gallardo was a criminal, but no one had ever accused him of being stupid. He knew the DEA lusted for him. They wanted his ass dead or in prison. Gallardo, attempting to lower his exposure, moved his family to Culiacan. As soon as he arrived, he called for a high-level meeting. All the Big Wheels of the various gangs in Guadalajara showed up. Gallardo informed the gang leaders that he was stepping out of the limelight. He was still the Boss of Bosses, and they still had to pay tithes. Gallardo wasn’t giving up his rightfully due share of the profits. Only now, instead of being both the Chief Executive Officer and Chief Operating Officer, he would simply be the CEO. Day-to-day operations would be handled by territorial leaders. In other words, Gallardo was delegating authority.

Tijuana, considered the crème de la crème of the territories, was given to Gallardo’s nephews. Nepotism was nothing new among the gangs; it was considered standard operating procedure. The nephews, the Arellano Felix brothers, would control and operate out of Tijuana, which came to be called the Tijuana Cartel. What would become the Juarez Cartel was given to Amado Carrillo Fuentes. Fuentes owned and operated twenty-seven Boeing 727s, in which he flew drugs into Mexico. After flying the drugs in, the planes were loaded with cash, which was flown out for laundering.

Miguel Caro Quintero was given Sonora, which was just south of Arizona. Thus was born the Sonora Cartel. And the Gulf Cartel, the territory around Matamoros, was given to Juan Garcia Abrego. The territory between Tijuana and Sonora, which was called the Sinaloa Cartel, was inherited by Joaquin “Shorty” Guzman Loera and Ismael Zambada Garcia.

All of the assigned cartels would be subservient to the Guadalajara Cartel, which would function as Gallardo’s administrative organization. The administrator was Hector “The Blond” Palma Salazar. Felix Gallardo would be the intermediary between the Colombian Cartels and the Mexican Cartels.

Unfortunately, the reorganization of his drug empire didn’t work out quite as well as Gallardo had envisioned. For one thing, Gallardo didn’t know how to maintain a low profile. He doled out vast amounts of cash to local charities and hung out with well-known politicians, with whom he was frequently photographed at glittering festivals and parties covered by national media outlets. Gallardo became the subject of many popular songs – narcocorridas – that served to increase his notoriety. And, to make things worse, the cartels, especially the Sinaloa Cartel, thought they could do anything because they had law enforcement officials in their pockets. Most of the police were taking bribes to look the other way. Kidnappings, rapes and murders went through the ceiling. In fact, they went so high that the government couldn’t help but notice.

The heat was on.

The Mexican government, appalled at the atrocities committed by the cartels, began an investigation of the Mexican Cartels. The investigation revealed what was common knowledge: the police were corrupt. It was like cancer, spreading everywhere. Pressured by the DEA, the Mexican government decided to clean house. The Mexican army arrested Gallardo in 1989. Then they interrogated 300 members of the Culiacan police force. Seven officers were indicted for accepting bribes, while almost one-third of the rank and file police officers quit after being questioned.

Mexico would not extradite criminals to any nation where they could face the death penalty. Therefore, Gallardo was tried in a Mexican court. Sentenced to forty years in prison, Gallardo continued to run his empire from behind bars, where he was allowed to use a cell phone. Still, because Gallardo was essentially out of the loop, his organization sank into the quicksand of rivalries and greed. Avaricious for money and territory, the Mexican Cartels eyed each other with suspicion and jealousy.

The Sinaloa Cartel didn’t like the hand they had been dealt. In effect, they had only two ways to move drugs into the U.S., through Tecate and Mexicali, neither of which led to lucrative markets, like southern California or Arizona. The Sinaloa Cartel took a look around and considered their options. To the east was Sonora, but the Sonora Cartel had lots of men and lots of guns. The other option was Tijuana, controlled by the Arellano Felix brothers, who the Sinaloa Cartel considered easier pickings. So they went to war with the Tijuana Cartel.

Benjamin Arellano Felix ran the Tijuana Cartel. His brother, Eduardo, ran the financial side of the business, taking care of the money laundering. Ramon, a younger brother, functioned as the Tijuana Cartel’s enforcer. The oldest brother, Francisco, paid off politicians and police officers. Francisco, who was an ostentatious cross-dresser, owned five houses and a discotheque called Frankie O’s. In his heyday, Francisco was greasing palms to the tune of six million dollars per month. The Tijuana Cartel was atypical in that many of their gang members were from affluent middle-class families. They dressed in expensive, stylish clothing, spoke English, and were educated. Most of them eschewed tattoos. They transported heavy weapons into Mexico and drugs into the U.S.

The Tijuana Cartel employed a take no prisoners’ policy. They murdered indiscriminately. Their enforcer, brother Ramon, believed that terror kept people in line. Ramon’s favorite methods of intimidation included the Colombian Necktie, where he slit the person’s throat, and then pulled the tongue out through the slit; using plastic bags to suffocate the enemy; cutting off heads; immersing people in acid baths; and what was called “carne asada,” where people were immolated on piles of burning tires.

When the Sinaloa Cartel tried to move in on the Tijuana Cartel’s territory, they discovered the pickings weren’t as easy as they thought. Things got bloody real fast, and the Sinaloa Cartel realized they had pulled the tail of a tiger. In an effort to escape a no-win situation, Shorty Guzman, head of the Sinaloa Cartel, called for a meeting with the Arellano Felix brothers. The two cartels met and negotiated. The Arellano Felix brothers held the winning hand and knew it. In the end, they permitted the Sinaloa Cartel to move product through Tijuana, but the Sinaloa Cartel had to pay a hefty tariff for the privilege. The brothers also insisted on total access to the Mexicali smuggling route into the U.S.

The deal was set.

Only Shorty Guzman didn’t like the deal. Providing his men with Federales uniforms and automatic assault rifles, Shorty ordered them to hit a disco in Puerto Vallarta. The disco was owned and operated by a close friend of the Arellano Felixes. Shorty had reliable information that the Arellano Felix brothers would be at the disco. The Sinaloa gangsters rushed into the disco, weapons blazing. Hearing the shooting, the Arellano Felix brothers realized what was going on. Running to the nearby bathroom, the brothers used the sink as a ladder to the bathroom’s skylight. Smashing through the skylight, they climbed onto the roof of the disco. Jumping down, they fled into the night.

Shorty’s costumed men killed nineteen people, eight of which were members of the Tijuana Cartel.

Livid with anger, the Arellano Felix brothers plotted their revenge. In May 1993, they put their plan into action. Learning that Shorty Guzman would be in a white Mercury Grand Marquis at the Guadalajara International Airport, Ramon sent hit men from the Tijuana Cartel to kill Guzman. The hit men set up an ambush for the car. When it arrived, the hit men deluged the car with bullets from automatic weapons. The two men in the car died on the spot, along with five other travelers who had the bad luck to be in the field of fire.

Shorty Guzman was not in the car. The man the hit men thought was Shorty Guzman was none other than a Cardinal in the Catholic Church, Cardinal Juan Jesus Posadas Ocampo. Since most Mexicans were Catholics, the people of Mexico were shocked and horrified by the murder. As details of the tragedy emerged, it was the first time many Mexicans heard the term “drug cartels.” The news media ran feature stories on the cartels, along with stories about the Arellano Felix brothers and Shorty Guzman. The fact that these cartels could ruthlessly murder a Cardinal of the Catholic Church spoke volumes about their power and lack of morality. Indignant at the government’s seeming impotence, the people of Mexico demanded justice.

An Excerpt from