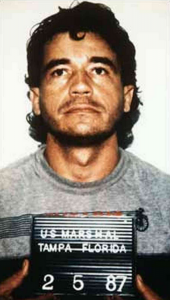

*This is an excerpt from Crazy Charlie:Revolutionary or Neo-Nazi? A book about Carlos Lehder from the Medellin Cartel By Ron Chepesiuk

In September 1981, a little more than a year after acquiring Norman’s Cay, Carlos Lehder left his day-to-day operations to subordinates and returned to his hometown of Armenia in Colombia. Gugliotta and Leen described Crazy Charlie’s situation at the time: (Lehder) “was twice divorced, unattached, and thirty-one years old; his millions were intact and burning a hole in his pocket. He decided to invest them in his home town of Armenia where he had not lived for fifteen years.”

In September 1981, a little more than a year after acquiring Norman’s Cay, Carlos Lehder left his day-to-day operations to subordinates and returned to his hometown of Armenia in Colombia. Gugliotta and Leen described Crazy Charlie’s situation at the time: (Lehder) “was twice divorced, unattached, and thirty-one years old; his millions were intact and burning a hole in his pocket. He decided to invest them in his home town of Armenia where he had not lived for fifteen years.”

Lehder left behind on Norman’s Cay a staging post for the Medellín’s smuggling operations that was just one of many such posts in Latin America. The size of the drug shipments had dictated the need for multi-ple routes from locations throughout Mexico and Lat-in America. By now, the Medellín Cartel, thanks in large part to Carlos Lehder, had a strong international operation that touched many countries, includ-ing, Bolivia, Peru, Honduras, the United States, as well as Canada and Europe, and some would say Asia.

Escobar, Lehder, and their colleagues had not ap-peared yet on Forbes magazine’s list of the world’s 500 richest people, but their illicit activities were making them tens of millions of dollars a day. By 1986, the Medellín Cartel controlled over 80 percent of the global cocaine market, shipping around fifteen tons of the drug to the United States daily.

Lehder was not shy about letting the world know his big plans for Armenia vowing, “I’m going to make this a real capitol, so that the entire world can visit it, and the fucking Yankees can finally appreciate what we have here.”

Back in 1978, Lehder, who, by then was garnering a lot of money from the drug trade, sent a letter to the governor of Quindio province, introducing himself as the president of a company from Nassau, Bahamas, named the Air Montes Company Ltd. According to Lehder, the business was dedicated to the interna-tional buying and selling of airplanes. He further re-vealed that his company donated airplanes to com-munities who lacked air transport, and guess what? The company had chosen the province of Quindio to receive a Piper Navajo 1968 which would arrive shortly. The plane did arrive during the Christmasholiday of 1978, much to the delight of the duly im-pressed local townsfolk.

Upon his return to Armenia, Lehder moved quickly. He set up a parent corporation, Cebu Quindio, which launched its first development project: the building of an “alpine” resort ten miles from Armenia. The re-sort would cater to the “world traveler.”

Upon his return to Armenia, Lehder moved quickly. He set up a parent corporation, Cebu Quindio, which launched its first development project: the building of an “alpine” resort ten miles from Armenia. The re-sort would cater to the “world traveler.”

Lehder further revealed that he would also build a $3 million complex called La Posada Alemana, which would include a small zoo, gourmet restaurant, a wine bar, a discotheque named after John Lennon, one of his idols, thirty well-equipped villas and sev-eral swimming pools. Lehder commissioned a well-known Colombian sculptor, Rodrigo Arenas Bentacur, to render a statue of a naked Lennon, with a gaping bullet hole in his back. La Posada Alemana was opened with much fanfare and a big party that local leaders attended.

Rodrigo Arenas Bentacur was just the beginning. Lehder looked for other investment opportunities in the province by traveling about in a ten-car caravan with a silver Mercedes and a gray Porsche equipped with the latest cellular telephone equipment in pur-suit of his objectives. Lehder was rich enough to keep three aircraft and two helicopters on permanent standby. He caused real estate prices in Armenia to skyrocket by literally buying up the city, condomini-ums, office buildings, and warehouses.

Lehder bought cattle ranches as well. One of them, the Hacienda Pisamal, contained about 700 acres.

Lehder’s investing caused quite a stir in Quindio province. Estimates of how much money he had to invest were put at $30 million to $270 million. When asked by one childhood friend where he got his money, Lehder explained matter-of-factly, “I worked in restaurants in New York. Then I sold cars and later airplanes in the United States.” Lehder would be asked that question many times during his return to Armenia and each time the answer was little bit different.

At the height of his empire, Lehder’s enterprise em-ployed 268 people, which was twice the number em-ployed by Bavaria, the beer company which had been Armenia’s biggest employer. With his high pro-file and evidence of power and money, Lehder be-came a celebrity and the media followed his every move.

At the height of his empire, Lehder’s enterprise em-ployed 268 people, which was twice the number em-ployed by Bavaria, the beer company which had been Armenia’s biggest employer. With his high pro-file and evidence of power and money, Lehder be-came a celebrity and the media followed his every move.

Lehder started his own newspaper, Quindio Libre, which he distributed nationally. The paper opposed anything American and praised Carlos Lehder, its publisher. Luis Fernando Mejia, the newspaper’s edi-tor, wrote: “Lehder, a man of a new era, captain of the seas and skies, landed in Quindio, home of the Indian chiefs, warriors and poets and idealists, at a time when dark clouds hang over the Republic.”

Lehder knew what good press could do for his image. So he shrewdly bought the favor of the Fourth Estate, legally, of course. He commiserated with the Colombian media about their miserable working con-ditions, lamenting that “it is not fair that journalists who represent the voice of reason and the flame of freedom in our democracy have to conduct their af-fairs in a place like this.” In a well-publicized event he presented a $3000 check to the local press asso-ciation’s president for improvements to the associa-tion’s building. When the improvements were com-pleted, the association, in gratitude, named one of their refurbished rooms, El Salon Bahamas, in Lehder’s honor.

The Roman Catholic Church was one of the benefi-ciaries of Lehder’s largesse. Indeed, one powerful church official, Bishop Dario Castrillon, did not hide the fact that he accepted donations from Lehder. Why shouldn’t they, the bishop argued, when the money went to the poor? The bishop, who later be-came an archbishop, even attended the opening of Lehder’s entertainment complex in Quindio in mid-1983, an act which appeared by many to be signal-ing the bishop’s blessing of the complex.

The Roman Catholic Church was one of the benefi-ciaries of Lehder’s largesse. Indeed, one powerful church official, Bishop Dario Castrillon, did not hide the fact that he accepted donations from Lehder. Why shouldn’t they, the bishop argued, when the money went to the poor? The bishop, who later be-came an archbishop, even attended the opening of Lehder’s entertainment complex in Quindio in mid-1983, an act which appeared by many to be signal-ing the bishop’s blessing of the complex.

But Lehder was a man of excesses, a hedonist who could not control himself, and the locals eventually soured on their generous benefactor. The locals real-ly didn’t like the impact Lehder was having on their youth. Youngsters seemed to idolize Lehder, routine-ly referring to him in the street as Don Carlos. The La Posada Alemana’s discotheque became notorious for drug use, and there were reports of naked young men and women chasing each other on the grounds at all hours of the night. Rumors abounded that as many as twenty young women from prominent local families had run away to stay with Lehder. It was al-so rumored that Lehder had gotten four or five of Armenia’s young girls pregnant.

Local charities began turning down Lehder’s dona-tions, while Armenia’s most prominent social clubs denied him admission. Lehder angrily claimed that the rejection was political. “The Armenia aristocracy doesn’t want me here because I came to serve the people and not to serve them (the aristocracy),” he complained.

In retaliation, he organized his own political party: The Latin National Movement.

The Latin National Movement was modeled on Hitler’s National Socialist Party, and it included the equivalent of Hitler’s youth auxiliary. Lehder attracted crowds of up to 10,000 people, many of whom were enticed to come by the drug lord’s distribution of $5 bills at his rallies. Its platform affirmed that the people had the right to possess small amounts of marijuana and reiterated its opposition to the extradition of drug traffickers from Colombia to the U.S. “Marijuana is for the peo-ple,” the Movement proclaimed.

Lehder went further and made cocaine trafficking the party’s central campaign theme. Lehder declared, “Cocaine is for milking the rich.” In one bizarre radio interview Lehder claimed that the profits from cocaine trade have actually been channeled towards the common people in Colombia and that’s why the country’s oligarchy was envious.

In other public addresses and appearances, Lehder made many bizarre comments. For instance, he claimed that Colombia’s cocaine traffickers were no different than the U.S.’s prominent Kennedy family that got rich smuggling booze during Prohibition. Critics should first look at how Colombia’s elite ac-quired their wealth before casting stones at him, Lehder argued. He claimed he was not materialistic and only interested in the welfare of Colombia, even though evidence of his greed and excesses were all around him.

In other public addresses and appearances, Lehder made many bizarre comments. For instance, he claimed that Colombia’s cocaine traffickers were no different than the U.S.’s prominent Kennedy family that got rich smuggling booze during Prohibition. Critics should first look at how Colombia’s elite ac-quired their wealth before casting stones at him, Lehder argued. He claimed he was not materialistic and only interested in the welfare of Colombia, even though evidence of his greed and excesses were all around him.

Lehder did not know it but, by not being able to keep his big mouth shut, he was sowing the seeds of his own destruction. As Simon Strong, the author of Whitewash: Pablo Escobar and Cocaine Wars, ex-plained. “It was Lehder’s desire to be a public figure that would trigger his downfall. It meant that he car-ried the brunt of any offensive against the traffickers and enabled him to be made into a scapegoat—which would prove just as useful to his colleagues as it would be to the Colombian and U.S. governments.”

This book is available on Amazon

If you like this article then check out The Top Ten Mafia Murders.