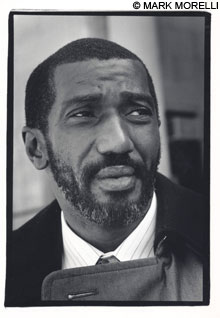

God and the Crack Era: The Rise and Fall of Darryl Whiting

God and the Crack Era: The Rise and Fall of Darryl Whiting

Boston’s crack era began in earnest in late 1986, when Darryl Whiting stepped into Roxbury’s Orchard Park projects for the first time. The jewels he wore, rumored to be made from a huge diamond he brought back from Africa, seemed to blind the whole city to what was coming.

They already called him God. The nickname came from his religion; he’d joined the Nation of Gods and Earths when he was 12 years old. Whiting was an early member of the group known as Five Percenters and experienced his conversion in New York City’s infamous juvenile detention facility Spofford Youth House. The religion’s founder, Clarence (13X) Smith, sponsored Whiting upon his release from jail.

When he was 16 and still in high school, he climbed into a car with a friend. The car happened to be stolen. The friend got probation. Whiting got 36 months at Rikers Island Reformatory. “They tricked me into taking a youthful offender,” he said years later. “They took three years of my life.”

After he was out for about half a year, he robbed a little store while carrying a gun. “I was a stick up kid,” he says. “From there I just started robbing everything, banks, supermarkets, drug dealers.” He did six years of a 12-year stretch. In prison he took up engineering and mechanical drawing and got his high school equivalency.

After his release, he attended La Guardia Community College in Queens and studied business but he never graduated. “I didn’t have time to study hard, to participate in class between trying to survive, so I would go over there and gather what I could to help me along in life,” he said.

He and a partner started a small contracting firm. Sheetrocking, masonry and painting. After a series of arrests – including one for the attempted murder of a police officer – Whiting and a group of friends moved to Boston, a city he had once visited on a ski trip. “New York had it out for me,” he told a reporter. He moved there in 1986 “to venture on, try out new ideas, because New York definitely was not letting me get at it.”

Whiting relocated to Boston on the eve of a boom in the cocaine trade. But it was not until he built his $11 million empire that the full force of the crack epidemic hit Boston. By the time he was done, the poorly maintained street around Orchard Park projects known as Bump Road was a 24-hour cocaine depot that grossed as much as $100,000 a day.

‘Classic Big-Time Drug Dealer’

Mann Terror, an Orchard Park native and member of the Boston rap group Wiseguys, was 12 when Whiting and a small group of New York gangsters first entered Orchard Park.

Whiting eventually introduced almost one hundred young men from his old Queens neighborhood to Orchard Park over a four year period. The young dealers usually arrived in Boston in groups of two and three. They came for different reasons; Kenneth (Shyan) Bartlett wore out his welcome in New York after years of wild behavior that included shootings and drug robberies. Others wanted to get out of Queens after the murder of Edward Byrne, a rookie New York City cop shot as he sat in his patrol car outside a witness’s home in the South Jamaica neighborhood of the borough. The murder, ordered by an imprisoned kingpin, became a flash point in the history of the War on Drugs but more immediately it sent a stream of dealers to Boston. “After those dumb motherfuckers killed a cop, I put a note on G’s windshield and said, ‘Bring me to Boston,’” said an ex-dealer. When they got to Boston, Orchard Park residents called them the New York Boys.

On arrival, Whiting’s MO for establishing a beachhead was simple: he found a series of vulnerable women — usually single mothers — and convinced them, through bribes or threats, to let him stay with them and run drugs out of their apartments. The first was a woman known as Miss Carol.

“Miss Carol was the older OG lady in the projects,” said Mann Terror. “Everybody would go through her house, smoke a little weed. When [Whiting] came in through her it wasn’t like they took the project over. They just started a little operation.”

Women would eventually suffer the worst scars of the crack epidemic. In contrast to heroin, where addicts were three fourths men, females gained a perverse equality in the 1980s when they made up half of crack addicts.

Gregory Davis, a substance abuse counselor with the Boston Housing Authority, said the drug’s effects on women meant black families paid the price. “The anchor, the person who held the family together was the woman. All the pressures she had on her, all of a sudden she checked out this thing called crack and she never was able to get back,” Davis said. “Crack was the final straw that destroyed the black family.”

In Orchard Park, Mann Terror says he saw an immediate change. “I saw the project go from an ok place to live to fucked up real fast after crack.” Addicted women were supplied with a continuous stream of crack in exchange for around-the-clock sexual services to dealers.

Amidst the misery, Whiting was building a myth that he was an all-powerful figure, according to former federal prosecutor Paul Kelly. “Darryl was a big, physical, athletic-looking guy,” Kelly recalls, “over six foot two, sharp dresser, deep voice, rode around in a Mercedes Benz, always wore dark glasses and a leather coat. Very quickly if you saw him, you’d think: classic big-time drug dealer. And he seemed to like that.”

To young project residents, Whiting’s gangster pedigree was awe-inspiring. “He was that dude,” says Mann Terror. “He brought that energy. When God walked through the projects it was like everything just kind of stopped.”

To Boston’s growing gang culture, though, the New York Boys were outsiders in Nike sneakers who had overstepped their bounds into a territory where Boston gangbangers wore Adidas. One New York drug dealer was shot when he wandered into an area controlled by the Intervale Street Posse, and two more were severely beaten when they tried to sell drugs in Columbia Point projects. But when local Grove Hall drug dealers tried to retake some of the ground lost to the New York Boys, a New York enforcer named Chill Will arrived to deliver a fatal message — shooting one of two cousins to death, and wounding the other.

In a recent phone interview from federal prison, Whiting painted himself less as an instigator of the city’s crack wars than a negotiator. “I took on somewhat of a mediator role for conflicts between New York and Boston dudes,” Whiting said. “Before I introduced the New York dudes to Boston there were certain things that they had to agree to. Because dudes in Boston, they weren’t having it — they’d run them right out of town, bag ’em up, and the whole nine. So we set an agreement. When [New Yorkers] come [to Boston], don’t try and take over the whole town, just sell coke up there and let them sell the heroin and the reefer. Also, don’t travel out of the Orchard Park area. Don’t go to other projects trying to sell shit, because those gangs will run you right out. Finally, don’t get involved with those guys’ girls. That was the agreement.”

In a recent phone interview from federal prison, Whiting painted himself less as an instigator of the city’s crack wars than a negotiator. “I took on somewhat of a mediator role for conflicts between New York and Boston dudes,” Whiting said. “Before I introduced the New York dudes to Boston there were certain things that they had to agree to. Because dudes in Boston, they weren’t having it — they’d run them right out of town, bag ’em up, and the whole nine. So we set an agreement. When [New Yorkers] come [to Boston], don’t try and take over the whole town, just sell coke up there and let them sell the heroin and the reefer. Also, don’t travel out of the Orchard Park area. Don’t go to other projects trying to sell shit, because those gangs will run you right out. Finally, don’t get involved with those guys’ girls. That was the agreement.”

But Whiting was more likely to surround himself with triggermen than peacekeepers. Enforcers like Steven (Mohammad) Wadlington, William (Cuda) Bowie, and Kenneth (Shyan) Bartlett still inspire fear in Orchard Park twenty years later; residents and police recall grisly murders, including one in which the victim was tortured and dismembered by New York Boys high on PCP.

Bartlett, in particular, cut an imposing presence, with his bodybuilder’s physique and far-away stares. “Shyan, he was the scariest motherfucker in the world,” says Mann Terror. “When he came around everyone held their breath, scared.”

“Anyone who encountered Kenny Bartlett on the streets of Roxbury would have been terrified,” says Kelly, the former federal prosecutor.

Whiting held these killers out as threats but publicly insisted he had nothing to do with murder. “I’m a religious man, right,” he told a reporter. “And I try to abide by the 10 Commandments as much as possible. And one of the strongest Commandments is ‘Yo, thou shall not kill.’ As the Commandments say is how I abide. As much as I possibly and physically can.”

“I Guess I’m Just a Humanitarian”

By 1989, Whiting had largely won the turf wars. The New York Boys were selling more than a kilo of cocaine a day in $40 and $60 bags; Whiting was getting a steady supply of high quality cocaine from a New York dealer allegedly supplied by a major Colombian cartel. Eight women were used as couriers, making multiple trips to New York City each week and carrying between 125 and 1,000 grams of cocaine back to Boston, according to federal investigators. Whiting said the New York Boys were paying $12,000 for a kilo and grossing $60,000….

This is an excerpt from George Hassett’s just released Gangsters of Boston, which is published by Strategic Media Books www.strategicmediabooks.com. Gangsters of Boston is available at www.Amazon.com, bookstores, as an e-book and at special discount price at the Strategic Media Books website

4 Comments

see

Ilovediyart.com

I read your post. It’s really very informative. Thanks for sharing information.

I read your post. It’s really very informative. Thanks for sharing information.

Narcotics ordeal which been “revealed” Silicon Beantown” it’s social frown majority believe. Lower income overall hidden middle class the affluent using narcotics. How can the Justice Dept derail the influence of mafia behind rising addictions! Why crime increase in Boston time get tougher I notice zombies the aftermath wasn’t. This way prior we need to address dangers of Drug world can we reduce “Addiction struggles” USA? I hope so lost life of once hopeful! Car Jacking,arson,robberies,extortions,rape and home evasions due Narcotics trade!