A couple of years ago a media investigation revealed that the US Office of the Pardon Attorney was broken. The Office of the Pardon Attorney (OPA) is housed within the Department of Justice (DOJ) and tasked with helping the president review applications for clemency. Clemency means an act of leniency or mercy and can take the form of a pardon, which usually restores a person’s rights after he has served his sentence, or a commutation which reduces a person’s prison sentence while they are still serving it, but doesn’t restore civil rights. Clemency is the last hope for thousands of federal prisoners serving excessive sentences, so it’s critical that the pardon attorney’s office give each case a full and careful review.

A couple of years ago a media investigation revealed that the US Office of the Pardon Attorney was broken. The Office of the Pardon Attorney (OPA) is housed within the Department of Justice (DOJ) and tasked with helping the president review applications for clemency. Clemency means an act of leniency or mercy and can take the form of a pardon, which usually restores a person’s rights after he has served his sentence, or a commutation which reduces a person’s prison sentence while they are still serving it, but doesn’t restore civil rights. Clemency is the last hope for thousands of federal prisoners serving excessive sentences, so it’s critical that the pardon attorney’s office give each case a full and careful review.

“The pardon attorney’s office says they look at every case carefully, but that’s not true,” Sam Morison, a long time staff attorney at the OPA told Pro Publica and The Washington Post. “They are supposed to be a neutral arbiter. OPA is supposed to wear two hats- his client is the DOJ, but he also works for the president. The pardon attorney is supposed to give fair, neutral advice to the president. That ethic no longer exists. The pardon attorney’s office now only represents the prosecutorial function of the Justice Department. It has an agenda. They tend to view any grant of clemency not as a good thing, as a criminal justice success story, but almost as a default that you’re taking away something from what some good prosecutor achieved.”

Dafna Linzer, the Pro Publica writer who broke the story was shocked to learn from her investigation that over 7000 commutation requests between 2008 and 2012 had been denied and Morison spoke with firsthand experience of the institutional problems that led to the approval of just 12 commutations total, with over 11,300 rejections during the Obama and Bush administrations. This all strongly supported the allegations that the OPA was not giving applicants meaningful or individualized review. The emerging truths revealed exactly how the OPA’s failure seriously affected people’s lives and the sense of justice in our country. There was an outcry in the media, because every prisoner who submits an application for clemency deserves a fair and impartial review of his case. But it was clear this wasn’t happening.

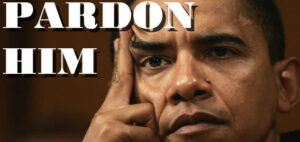

President Obama, the DOJ and the OPA were highly criticized in the press and President Obama took actions to investigate the claims being made. “We are asking and others have asked repeatedly for an investigation of the OPA because it is a complete disaster,” Julie Stewart, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums said. “The taxpayer funded office has failed in its sole responsibility to help the president analyze requests for federal clemency. By directing the administration to take a close look at the office, the president has shown that he understands the magnitude of the problem.” A full investigation was launched into the OPA’s misconduct. It was clear that the nation wanted the clemency process fixed, so that all prisoners could get a fair shot at relief from the President.

The New York Times complained that when it came to pardon power, there was no excuse for Obama’s lack of compassion and encouraged him to do much more. The founding fathers considered the pardon power an integral part of our system of separation of powers and checks and balances. Its presence in the constitution is premised on the notion that Congress and the courts are not always perfect. Under heavy criticism, Obama finally commuted the sentences of eight federal inmates in December 2013, who were convicted of crack cocaine offenses. They were all first time, nonviolent offenders who got caught up in the tough on crime federal sentencing rules that attached long sentences to crack cocaine involvement. One of those whose sentence was commuted was Clarence Aaron, whose plight was widely publicized.

“If they had been sentenced under the current law, many of them would have already served their time and paid their debt to society,” Obama said. “Instead because of a disparity in the law that is now recognized as unjust, they remain in prison, separated from their families and their communities, at a cost of millions of taxpayer dollars each year.” The eight commutations opened a major new front in the administration’s criminal justice policy intended to curb soaring taxpayer spending on prisons and to help correct what the administration has portrayed as unfairness in the justice system. The Obama eight became a compelling factor for those still behind bars, because a sense of hope was restored among those in prison serving lengthy sentences for nonviolent crimes.

“This would be a positive step toward righting the wrongs of our broken criminal justice system.,” Drug Policy Alliance spokesman Anthony Papa said. “With half a million people still behind bars on nonviolent drug charges, clearly thousands are deserving of a second chance.” With the first batch of commutations, Obama directed the Justice Department to improve its clemency process and recruit more applications from prisoners. “The President believes that one important purpose can be to help correct the effects of outdated and overly harsh sentences that Congress and the American people have since recognized are no longer in the best interests of justice,” White House counsel Kathryn Ruemmler said. “This effort also reflects the reality that our overburdened federal prison population includes many low-level, non-violent offenders without significant criminal histories.”

But due to our government’s policies and the broken OPA, many federal prisoners, who deserved clemency, were denied and overlooked. “I served 25 years,” Michael Santos, a former federal prisoner says. “But I was as ready for release as I ever would be after I served eight years, back in 1995. By 1995, I had earned a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree while serving the first eight years. I had a strong support network that would’ve helped transition into society as a 31-year-old, well-educated man. I would’ve been ready to begin building a career as a law-abiding, taxpaying citizen. Instead, I served another 17 years.”

There are over 3,500 pending pardon and commutation applications at the White House right now and good candidates for clemency are not only crack dealers. Attorney General Eric Holder has made proposals to expand the clemency program to a larger field of eligible individuals. The effort is part of a strategy to reduce the federal prison population and reverse past sentencing policies that doomed many offenders, including thousands of non-violent offenders like Michael and myself to disproportionately long terms. “We pay much too high a price whenever our system fails to deliver the just outcomes necessary to deter and punish crime, to keep us safe, and to ensure that those who have paid their debts have a chance to become productive citizens,” Holder said. “Once these reforms go into effect, we expect to receive thousands of additional applications for clemency.”

By May of 2014, the Justice Department set the new clemency conditions. They announced new rules that would potentially make thousands of federal inmates eligible for presidential grants of clemency, including requirements that candidates must have served at least ten years of their sentence, have no history of violence, no ties to criminal organizations, gangs or cartels, have no significant criminal records, have demonstrated good conduct in prison and be serving terms in federal prison that would probably receive a substantially lower sentence today if convicted of the same offense.

These criteria fit people like Michael and me, but for us it is too late. He is already home and I am on my way to a halfway house. The DOJ even sent out a survey on TruLincs, the Bureau of Prison’s (BOP) in house computer system that allows prisoners to send emails to approved people and download songs on their MP3’s. The survey, which over half of the prisoners locked up in the BOP filled out, said it was looking for clemency applicants, but no one has been let out yet. Until the prisoners of the War on Drugs are let out, it is just empty rhetoric to me. But the politicians continue to hype up the alleged changes.

“I am very encouraged by the prospect that these new clemency criteria will give deserving non-violent drug offenders a second chance at freedom, improve our justice system and save taxpayers money,” Rep. Steve Cohen, D-Tennessee said. Up to 13 percent of the federal prison systems 216,000 inmates have served 10 years or more, but not all would qualify for consideration based largely on their criminal histories. But there are still thousands who do qualify and should be let out of prison now.

“There are more low level, non-violent drug offenders who remain in prison, and who would likely have received a substantially lower sentence if convicted of precisely the same offense today,” Deputy Attorney General James Cole said. “This is not fair and it harms our criminal justice system. This clemency initiative should not be understood to minimize the seriousness of our federal criminal laws. However, some of them, simply because of the operation of the sentencing laws on the books at the time, received substantial sentences that are disproportionate to what they would receive today.”

Let’s hope this plan works and victims of the drug war can go home to their families and resume their lives. Our federal sentencing laws have shattered families and lives and wasted millions of taxpayer dollars warehousing first-time, non-violent offenders for decades of their life, with no chance of parole. Michael Santos and myself are just two of the many prisoners who should have been given a second chance long ago. The President now has a momentous opportunity to correct the injustices of the drug war in individual cases.

“What additional benefit did taxpayers receive in return for confining me for 25 years rather than releasing me after I served eight years?” Michael asks. “Multiply those costs by the number of people who no longer need to be locked up in deferral prison and tax-payers can see real government waste. It’s a waste not only in financial resources, but in human resources.

“We confine way too many people in our federal system and those people serve sentences that are far longer than necessary. Taxpayers should demand a mechanism that would lead to the release of non-violent offenders who’ve been sufficiently sanctioned for their offenses.” A mechanism has finally arrived, in the press at least, but will it really happen or is it just more empty rhetoric from the Drug War debacle. Let’s hope this administration follows through on their words.